For over two decades now, manufacturing and process plants have been seeing their older workers retire. As luck would have it, economic issues and the pandemic have slowed this exodus of institutional knowledge, but it is once again picking up steam. Many of the more elderly workers either died due to Covid-19 or their health declined so that they simply couldn’t keep working in physically demanding jobs in manufacturing or process companies. Then, there is the Great Resignation, as it is being called, of people who simply do not want to do the work they were doing before the pandemic. There are a number of reasons why this is true. Those reasons cluster around quality-of-life issues. Working too much overtime. Working split shifts. Jobs with no hope of promotion. No raises, on top of poor wages to begin with. The reasons abound, and the result is that many people who can do other work are leaving manufacturing and process industries in droves.

The vanishing of institutional knowledge located in the heads of these workers has been vexing managers for many years. Many attempts have been made to try to capture what these workers know about operating their plants, with very limited success. This hasn’t worked very well.

The older workers now retiring were the last generation of workers who operated the plant either manually, or in open loop mode, with an operator in the loop. They learned how by doing it—it is called motoric learning. They sometimes learned by rote without understanding why they were doing the things they did. Sometimes, they operated the plant or did maintenance by intuition. Sometimes, they used other senses, like hearing, smell, even taste to tell them the status of the plant and its assets. Often, they were taught by oral tradition from their own elders in the plant, and like the children’s game of “telephone” the transmission of what to do when became a little garbled. This led to sometimes magical thinking. “Before I turn the valve operator, I have to hit it with the wrench. Why? Joe taught me to do that thirty years ago. I don’t know why. It just works.”

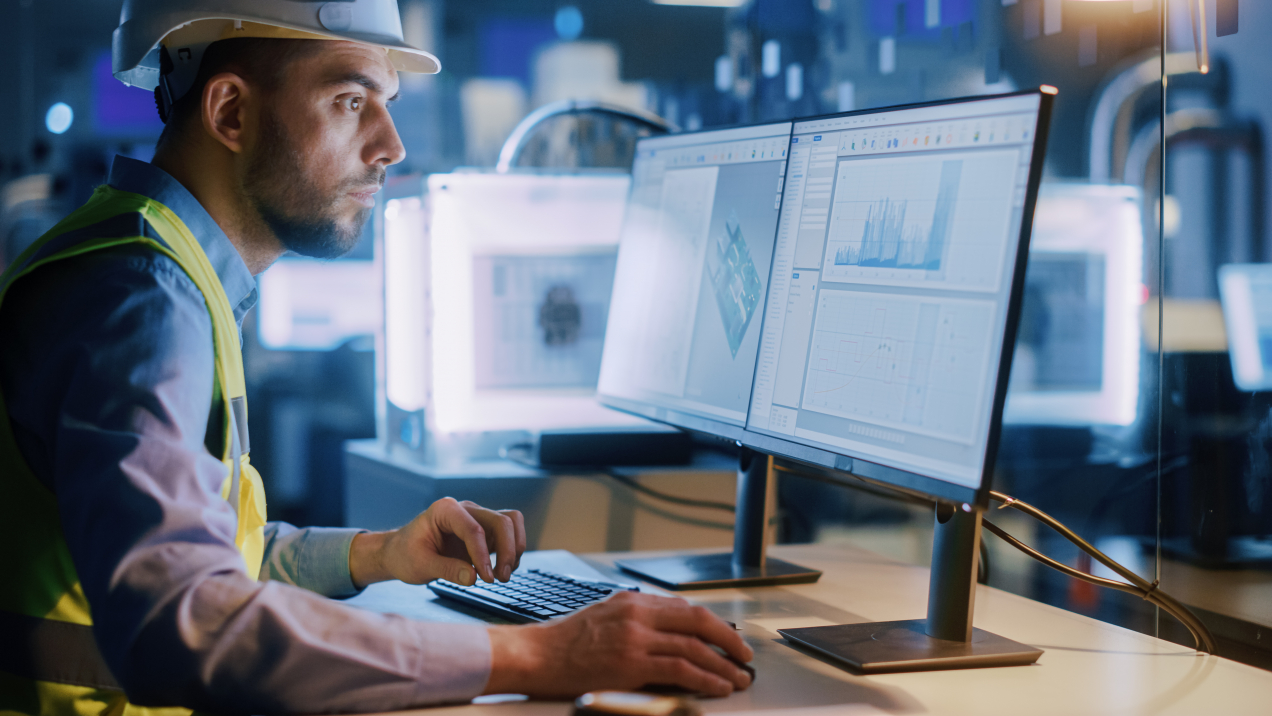

On the engineering and operations side, it has been easier to capture the institutional knowledge as the older workers leave than it has been on the maintenance side. Some of this is better documentation, but mostly it has been the growth and development of control systems. Control systems, whether machine control in manufacturing or batch or continuous control in process plants have provided a ready-made training tool for new operators. They are usually well documented, and in many industries, the use of simulation systems for training is well documented and effective.

Not so much on the maintenance side of things. Maintenance failures are not as well documented as control successes are. Many plants are still operated in “run to failure” mode, instead of having active maintenance management programs. In run to fail mode, the newer operators never know what is going to go first. They don’t have the experience of their older comrades, who can do things like hear the noise of cavitation from a pump and understand what it is and why it is happening. Or see and hear the specific type of vibration that signals a motor in distress. Or be able to feel the pipe swelling because it is significantly corroded inside. All of these are the knowledge that younger operators do not have.

The good news is that there are emerging technologies that will allow plants to substitute for the institutional knowledge that has left the workforce. “Run to fail” operations have become far too expensive for most industries, since maximizing uptime maximizes production. Tools to enable maintenance management have made predictive and prescriptive maintenance possible, thus lowering costs, increasing uptime, and thereby increasing production and revenue.

Those tools give maintenance managers ways to codify the knowledge of their operators and technicians the way designing control loops and ladder diagrams did for the operations side of the plant.

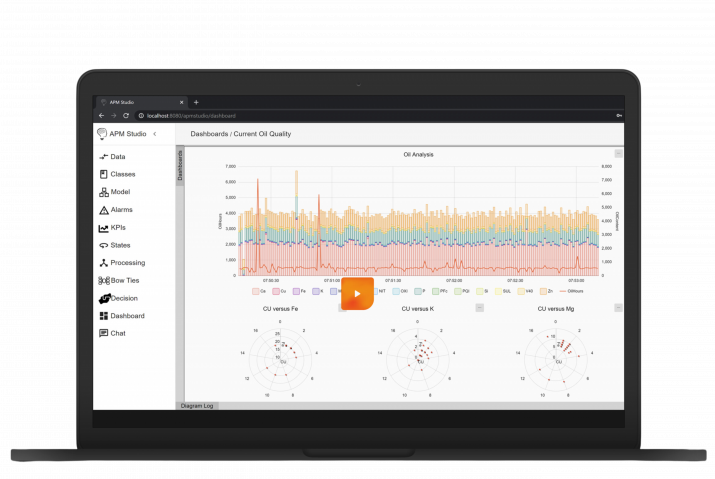

Tools like UReason’s APM Studio can be used to replicate the institutional knowledge as it leaves the plant, by having the experienced operators and engineers participate in producing the cause/consequence models and training the AI software to be able to recognize what a strange vibration could lead to. The coupling of large quantities of data and the computing power of Artificial Intelligence will turn maintenance into the prescriptive maintenance technologies that keep plants running and keep profits up.

Click here for an eBook that explains how this works, and click here to have a UReason APM expert contact you for a demonstration.